Actors & Activities

Last Updated: July 17, 2009

This section presents the main mechanisms of transitional justice (criminal prosecutions, truth commissions, reparation programs, vetting processes, and amnesties) as well as the supporting activities that are conducted by different actors in the field. It also introduces the main actors (both insiders and outsiders) engaged in these processes and some of the issues created by their interaction.

Key measures of transitional justice

Transitional justice in post-conflict societies consists of a number of key well-known measures. These measures are:

- Criminal prosecutions;

- Amnesties.

- Truth seeking mechanisms;

- Reparation programs;

- Vetting processes.

Reconciliation processes are also intimately linked to those mechanisms, although they intervene at a broader non-judiciary level.

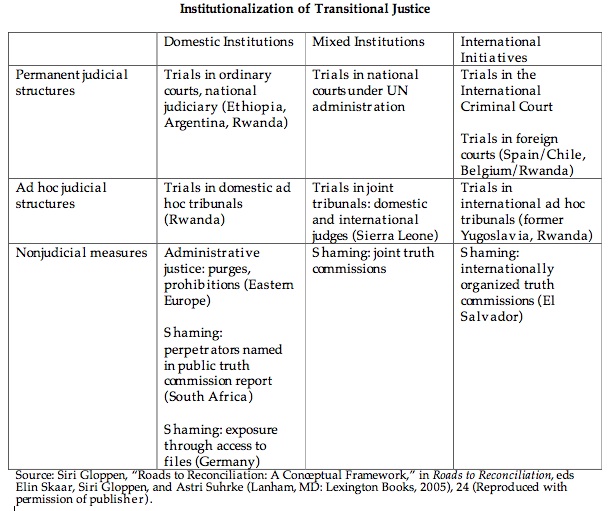

The table below, conceived by Siri Gloppen, researcher at Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI), an independent centre for research on international development and policy in Norway, offers an overview of the different forms of institutionalization of these mechanisms and a few illustrations for each category.

For the most thorough country-specific database on past and current transitional justice mechanisms, see: "Justice in Perspective: Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation in Transition" (a project of the South African Center for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR)

[Back to Top]

Criminal prosecutions

Prosecutions form one of the central elements of an integrated transitional justice strategy, aimed at moving a society beyond impunity and a legacy of human rights abuse. Significant advances in criminal accountability have taken place over the past two decades. However, impunity continues to be the norm for serious violations of national and international law, while successful prosecutions are the exception.1

There are four types of criminal prosecutions in relation to post-conflict contexts:

- National (or domestic) prosecutions;

- International tribunals;

- Hybrid courts;

- Transnational prosecutions.

National (or domestic) prosecutions

National (or domestic) prosecutions of individuals responsible for serious human rights violations have been extremely rare. A few prosecutions took place only in Greece in 1974 after end of the military dictatorship and, more recently, in Argentina, where nine of the highest leaders of the Junta were brought to trial, five of whom were found guilty. These trials prosecuted high-level perpetrators. In some cases, lower-level perpetrators have been prosecuted domestically, including by a special court system, such as the gacaca courts in Rwanda.

Go to the official website:http://www.inkiko-gacaca.gov.rw/index.html

International tribunals

International ad hoc criminal tribunals are temporary bodies designed to prosecute individuals responsible for violations of international human rights and humanitarian law. Such tribunals include the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). A recent development has been the establishment of the International Criminal Court (ICC), which is the first permanent tribunal with jurisdiction over genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. It tries only the persons accused of the most serious crimes of international concerns. The ICC Prosecutor is currently conducting investigations and prosecutions against high-level prosecutors in the cases of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, Central African Republic and Darfur (Sudan).

It is important to note that the ICC is a court of last resort. It will not act if a case is investigated or prosecuted by a national judicial system unless the national proceedings are not genuine; for example, if formal proceedings were undertaken solely to shield a person from criminal responsibility. The statute of the Court states that it will assume jurisdiction only where States are "unwilling or unable genuinely" to investigate or prosecute themselves.2 Moreover, the Court will have jurisdiction only where States are parties to the Rome Statute or in situations referred to it either by a State itself or by the United Nations Security Council, and then only over crimes committed after July 2002.

Hybrid courts

A new area of innovation in international justice has been the creation of so-called "hybrid" courts that mix international and national judges and other judicial personnel. Hybrid courts are said to constitute the "third generation" of international criminal bodies. The first generation consisted of the post-World War II Nuremberg and Tokyo military tribunals, and the second being the ad hoc tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda and the International Criminal Court. The Special Court for Sierra Leone, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, and the Special Panels for Serious Crimes in East Timor, are all cases of hybrid mechanisms of criminal prosecution.

Transnational prosecutions

Another recent development in international justice is the practice, based on the principle of universal justice, whereby states claim criminal jurisdiction over individuals whose alleged crimes occurred outside the borders of the prosecuting state, and regardless of nationality, country of residence, or any other relation with the prosecuting state. These instances are known as transnational (or extraterritorial) trials. The most notorious examples of this are Spains indictment of former Chilean leader Augusto Pinochet and Belgiums indictment of former Chadian leader Hissene Habre.

For a discussion of the strategic challenges of prosecuting perpetrators of crimes such as genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, see the report:

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Rule-of-Law Tools for Post-Conflict States: Prosecution Initiatives (New York and Geneva: United Nations, 2006)

This tool presumes that long-term and sustainable solutions to impunity should aim mostly at building domestic capacity to try these crimes. It therefore focuses on the strategic and technical challenges that these prosecutions face domestically. In some situations, however, it is not possible to act through the domestic legal system, because of a lack of capacity or political will. Therefore, this tool lays out some of the policy considerations that pertain to internationalizing the process, for instance through the creation of international or hybrid tribunals.

Five guiding considerations are recommended to be applied to all prosecutorial initiatives (whether domestic or with international assistance): 3

- Initiatives should be underpinned by a clear political commitment to accountability that understands the complex goals involved.

- Initiatives should have a clear strategy that addresses the challenges of a large universe of cases, many suspects, limited resources and competing demands.

- Initiatives should be endowed with the necessary capacity and technical ability to investigate and prosecute the crimes in question, understanding their complexity and the need for specialized approaches.

- Initiatives should pay particular attention to victims, ensuring (as far as possible) their meaningful participation, and ensure adequate protection of witnesses.

- Initiatives should be executed with a clear understanding of the relevant law and an appreciation of trial management skills, as well as a strong commitment to due process.

Amnesties

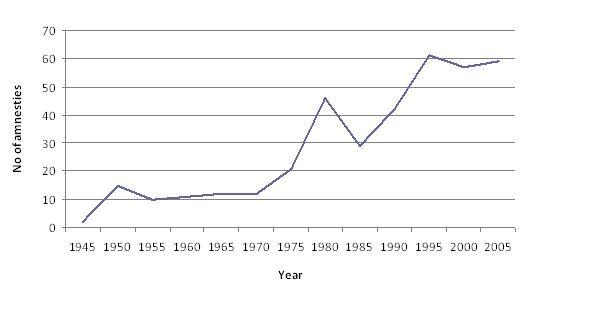

Despite the existing of a global justice cascade (or a significant increase in the number of criminal prosecutions and truth commissions over the last several decades), another central feature of the current landscape of transitional justice is the continued use of amnesties in transitions from armed conflict to peace. According to one estimate, 420 amnesty processes have taken place since World War II, and over 66 amnesties occurred between 2001 to 2005, showing that "amnesties have continued to be a political reality despite international efforts to combat impunity."4

The following graph, developed by Louise Mallinder, from Queen's University Belfast School of Law, corresponds to data on 401 amnesty processes. Because this graph is intended to contrast the frequency of trials with amnesty laws, "reparative amnesty laws" which applied to non-violent political offenders or draft dodgers and deserters were excluded. Between January 2005 and December 2007 a further 24 (non-reparative) amnesty laws were introduced.

Source: Louise Mallinder, Amnesty, Human Rights and Political Transitions: Bridging the Peace and Justice Divide (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2008), 19 (Reproduced with the authorization of the author).

There are several types of amnesties: self-amnesties, negotiated amnesties, total (blanket) amnesties, and conditional amnesties.

There seems to be an emerging consensus that amnesties should be reserved for "lesser crimes" (not genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes) committed by mid- and low-level perpetrators, whereas criminal prosecutions should target those with the "greatest responsibility" for massive or systematic crimes.5

The very idea that amnesties are transitional justice mechanisms can be highly contentious, as they may appear as "do nothing" approaches. A detailed analysis of the amnesty process implemented by the South African truth and reconciliation commission has also shown the limits of such mechanisms, in particular in their attempt at separating "politics" and "crime" for the purposes of building reconciliation at a political level. Graeme Simpson, a founder and former executive director of the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, in Johannesburg, noted: "One of the greatest flaws of the TRC was its failure properly to engage with the complex nature of criminality. Not only did the amnesty process ignore many of the complexities consequent upon the historical criminalisation of political activity, but it was also incapable of accommodating the extent to which the politicisation of crime represented the other side of the same coin."6 This analysis could be applied to many other contexts. However, amnesties remain largely used in transitional contexts as instruments for ensuring a transition from violent conflict to peace.

[Back to Top]

Truth seeking mechanisms

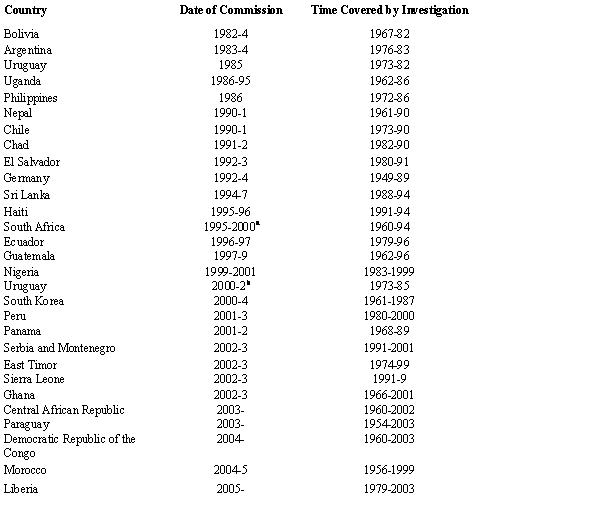

It is safe to say that "the truth commission has become a staple of post-conflict peacebuilding efforts,"7 with about thirty truth commissions established to date.

The following table offers an overview of the chronological development of the truth commissions and their development in post-conflict contexts over the last two decades (whereas they were previously more focused on post-dictatorial situations).

To this list, although in a different context, can be added the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Canada, created as a result of the court-approved Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement negotiated by legal counsel for former students, legal counsel for the churches, the Government of Canada, Assembly of First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations. The Commissions mandate is to document the truth of survivors, their families, communities and anyone who has been personally affected by the Indian Residential Schools legacy. The commission was established on June 1, 2008. This commission is exceptional by the focus of research: over 150 years (the last Indian Residential School was closed in 1996).

Source: Eric Wiebelhaus-Brahm, Truth Commissions and Transitional Societies: The Impact on Human Rights and Democracy. (Routledge, Forthcoming). Used with permission from the author.

For the most thorough online information about truth commissions, including online access to truth commission reports, go to United States Institute of Peace's Truth Commissions Digital Collection.

Truth commissions are non-judicial, official and temporary bodies established after a period of violent conflict or political repression to uncover and document massive or systematic human rights violations. Truth commissions are designed to promote restorative justice, wherein victims (and, less commonly, perpetrators) tell their stories with the aim of crafting a broader social narrative about the past.

It is important to distinguish truth commissions from another type of official inquiry into the past: historical commissions, or commissions of inquiry. In general, historical commissions are government-sponsored inquiries which are not "part of a political transition," but rather deal with earlier historical events and seek to clarify historical facts and pay respect to previously unrecognized victims or their descendants.8 Go to Memorialization, historiography and history education

The proliferation of truth commissions has given rise to an array of official names. Some commissions are called truth commissions, while others go by the name "truth and reconciliation commission." These commissions make reconciliation an explicit goal of their work (such as in Chile, Liberia, Peru, Sierra Leone, and South Africa). In still other cases, different names are used. The commission in East Timor, for example, was called the "Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation" (CAVR), and the one in Argentina was called the "Commission on the Disappeared." The term "truth commission" is the most inclusive one because, although commissions may variably promote other goals, they all share a common objective in the establishment of the truth.

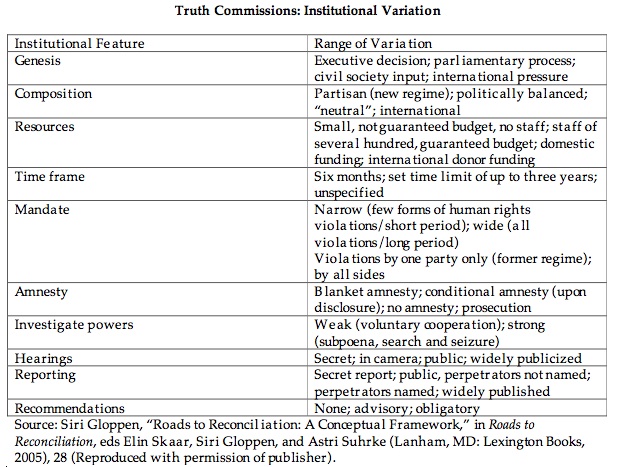

There is a great deal of variation among truth commissions in terms of mandates, resources, and investigative powers, reporting, and intended outcomes, among other factors. The table below, developed by Siri Gloppen, researcher at Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI), in Norway, offers an overview of the range of variation that can be encountered.

Perhaps the most well-know commission was the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which was also the most substantial one in terms of resources, mandate, and powers. During its operation from 1995 to 1998, the TRC gathered 23,000 testimonies from victims, perpetrators, and witnesses, 2,000 of which occurred during public hearings. The most distinctive aspect of the TRC was its power to grant amnesty to human rights violators in exchange for full disclosure--also known as a "conditional amnesty."9 The Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission was also substantial. It had a budget of 13 million dollars, a 500-person staff, and it collected the testimonies of almost 17,000 victims.10 Other commissions have not fared well, and some have been complete failures.

Societies emerging from a period of violent conflict may opt not to establish a truth commission for a variety of reasons.11 First, in some cases revisiting the past may be perceived as potentially destabilizing for fragile post-conflict environment, with the potential for a return to armed conflict. Second, there may be a lack of political interest in establishing a truth commission. Third, the state and society may consider other post-conflict tasks, such as economic reconstruction, to be of greater importance. Fourth, some post-conflict societies may choose to engage in other transitional justice mechanisms or local justice processes. Transitional countries that have chosen not to establish truth commissions include Cambodia, Mozambique, and Spain.

There are also real risks associated with establishing truth commissions.12 For example, truth commissions may be established for reasons other than documenting an accurate historical record. Instead, a truth commission may be used by the ruling regime as an instrument of political score-settling against its current or previous opponents. Or, a truth commission can be established as a convenient (and relatively cheap) way of bypassing other transitional justice processes, such as reparations for victims. Another risk is that truth commissions (or those establishing, running or promoting them) may set unrealistic goals that inevitably lead to widespread disillusionment with the broader peacebuilding process.

There are both constraining and enabling factors that affect the operation of truth commissions. Constraining factors include the weakness of civil society, fears about publicly testifying before a truth commission, the weakness or corruption of the justice system, and social polarization where certain sections of society identify with the perpetrators. Enabling factors, on the other hand, include political consensus, public support and civil society engagement, and adequate financial support.

The main activities/ stages of the work of a Truth Commission are:13

- Preparatory Phase

- Outreach

- Statement-Taking

- Research and Investigation

- Data Processing

- Public Hearing

- Emotional Support

- Final Report

- Follow-up Efforts

For basic principles and approaches to truth commissions (best practice guidelines), see Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Rule-of-Law Tools for Post-Conflict States: Truth commissions (New York and Genera: United Nations, 2006).

It is important to note that truth commissions, in particular when they make reconciliation an explicit goal of their work, are part of a more complex and multi-dimensional phenomenon encompassing several processes of addressing conflicting and fractured relationships in a society. These included a vast range of activities of which TRC is only one aspect.

[Back to Top]

Reparations

It is generally recognized that "both the demands of justice and the dictates of peace require that something be done to compensate victims."14 It is also clear that states have a responsibility under international law to provide reparation to victims of grave human rights violations. Reparation can be material, psychological, symbolic, or a combination thereof. Material forms of reparation include compensation payments, health insurance, pensions, and educational scholarships; psychological measures include trauma counseling; and symbolic measures include official apologies, monuments and memorials, and days of remembrance.

Go to Trauma, mental health and psycho-social well-being and Memorialization, historiography & history education

The Components of Reparations:15

- Restitution. The goal of restitution is to reestablish the victims status quo ante. Measures of restitution can include the reestablishment of rights, such as liberty and citizenship, and the return of property.

- Compensation. This is the essential and preferred component in reparations, especially at the international level. Compensation is usually thought to involve providing an amount of money deemed to be equivalent to every quantifiable harm, including economic, mental, and moral injury.

- Rehabilitation. This includes measures such as necessary medical and psychological care, along with legal and social support services.

- Satisfaction and guarantees of nonrecurrence. These particularly broad categories include such dissimilar measures as the cessation of violations; verification of facts, official apologies and judicial rulings seeking to reestablish the dignity and reputation of the victims; full public disclosure of the truth; search for, identifying, and turning over the remains of dead and disappeared persons; the application of judicial and administrative sanctions for perpetrators; as well as measures of institutional reform, all with the aim of providing some promise that such atrocities will not recur.

Reparations can also be symbolic.

Go to Reconciliation and Memorialization, historiography & history education

Reparation programs can serve as mechanisms of compromise. "In some post-conflict societies, systematic criminal prosecution of all those involved in the past oppression may threaten political stability and undermine democratic consolidation. On the other hand, requests by members of the previous regime that the past be simply forgotten are equally unacceptable. Reparation, which necessarily includes a form of sanctioning and honouring of victims rights, is therefore in itself a useful instrument of compromise. This is all the more true in those cases where an amnesty law denies victims the right to institute civil claims against perpetrators: a state reparation programme may counter, to some extent, the effects of the amnesty legislation."16

However, there are serious challenges associated with crafting reparation programs in post-conflict societies. As one expert writes, "the formulation of a comprehensive reparation policy is often both technically complex and politically delicate."17 First, in international legal terms, full restitution (or the restoration of the status quo ante) is the commonly recognized criterion of justice. In post-conflict or post-mass atrocity societies, however, it is virtually impossible to meet that criterion of full restitution because of the massive scale of abuses, the vast numbers of potential beneficiaries, victims, and low levels of socio-economic developments.

Second, as a leading expert on reparation observes, in some post-conflict societies, "it is likely that transitional governments will be particularly tempted to forego reparations in favor of development programs."18 Though development programs are undoubtedly crucial for the economic reconstruction of post-conflict societies, there is a key distinction between development programs and reparation programs. Development programs "do not target victims specifically...and try to satisfy basic and urgent needs, which means that their beneficiaries perceive them, correctly, as distributing goods to which they have rights as citizens, and not necessarily as victims."19 However, given their severely limited resources, governments may tend to conflate the two.

Third, the question of who qualifies as a victim is at the center of any reparation policy. The technical and political process of defining victimhood is bound to be highly contentious and potentially destabilizing. As the UN Secretary General's report states, "Material forms of reparation present perhaps the greatest challenges, especially when administered through mass government programmes. Difficult questions include who is included among the victims to be compensated, how much compensation is to be rewarded, what kinds of harms are to be covered, how harm is to be quantified, how different kinds of harm are to be compared and compensated and how compensation is to be distributed."20 In many cases, reparations policies have caused feelings of frustration among victims and their relatives.

The role of international actors is another contentious dimension of reparation politics in post-conflict societies. As scholar Pablo de Grieff observes: "Despite the expectations of many postconflict or transitional societies, the international community rarely provides significant resources to finance reparation initiatives. The main reason for this reluctance results from the fact that reparations benefits should...always involve a dimension of acknowledged responsibility, and thus the international community has often argued that reparations should be primarily a local initiative. As well, given that implementing a reparation programs always involves sensitive political decisions, the international community has little incentive to get involved in a potentially decisive arena."21 It has been found that the development of a reparations program depends in large part on the existence of broad coalitions in support of reparations.22

For practical guidelines on implementing reparations initiatives, see:

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Rule-of-Law Tools for Post-Conflict States: Reparations Programmes (New York and Genera: United Nations, 2006).

[Back to Top]

Vetting

Vetting refers to the formal process of identifying, removing or excluding individuals responsible for human rights abuses from employment in public institutions (primarily the police, army, prison services, and the judiciary).

Although vetting "has been mainstreamed by international organizations involved in post-conflict societies," in large part due to the growing emphasis on institution-building, it still "remains below the radar in many transitional societies, and has not garnered the same level of interest as criminal accountability or truth commissions; resources and international support for vetting practices remain at low ebb. "23 As a result, "the importance of vetting as a mechanism to correct the partiality, selectivity, and other limits of traditional transitional justice--for instance, through a joint consideration of institutional and personnel transformation--remains to be fully realized."24

In post-conflict societies, vetting is an inextricable element in the broader arena of institutional reform because vetting processes result in changes in the composition of an institution's staff, which may in turn affect that institutions culture and modes of behavior. By exerting such influence, vetting processes are meant to effect structural change and dismantle "networks of criminal activity"25 with the aim of making those institutions more trustworthy in the eyes of the general population. At the same time, vetting processes in post-conflict societies may be particularly prone to political manipulation because they engage thousands of people, take place away from public scrutiny, offer weak procedural guarantees, and entail some degree of control over public institutions.26

Go to Judicial and Legal Reform/(Re)construction and Public administration, local governance and participation

It is important to note that there is a fundamental difference between purging and vetting. As one expert notes, "purges differ from vetting in that purges target people for their membership in or affiliation with a group rather than their individual responsibility for the violation of human rights," as vetting processes are designed to do.27

As with all other transitional justice mechanisms, no standard vetting template exists for application in post-conflict societies. Rather, architects of vetting processes in post-conflict societies must make nine basic decisions:28

- Targets: What are the institutions and positions to be vetted?

- Criteria: What misconduct is being screened for?

- Sanctions: What happens to positively vetted individuals?

- Design: What are the type, structure, and procedures of the vetting process?

- Scope: How many people are screened? How many people are sanctioned?

- Timing and Duration: When does vetting occur and how long does it last?

- Rationale: How is vetting justified? What are the reasons for vetting?

- Coherence: How does the vetting relate to other measures of institutional reform? How does it relate to other transitional justice measures?

For a detailed analysis of vetting processes in post-conflict societies, see Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Rule-of-Law Tools for Post-Conflict States: Vettingan operational framework (New York and Genera: United Nations, 2006).

[Back to Top]

Supporting activities

A wide spectrum of activities at the international, national and local levels aims to support transitional justice (TJ) processes. This section focuses on six main types of supporting activities:

- Training and capacity-building of domestic TJ actors;

- Technical assistance, oversight and implementation of TJ mechanisms;

- Research, education and exchanges;

- Awareness raising and the media;

- Memorialization;

- Artistic and cultural endeavours.

Training and capacity-building

Post-conflict settings are often marked by low levels of domestic capacity and weak or nonexistent national institutions. In addition, widespread abuses by government actors may have discredited public servants who may have to undergo re-training or be replaced by other actors not associated with the conflict. As a result, much of the training of judges, law enforcement and investigation is carried out by outsiders who have taken part in similar processes elsewhere and are considered experts in their respective fields. While the presence of foreign trainers can lend legitimacy to national actors who may have been discredited by the conflict, they can also perpetuate the image of domestic incompetence and lack of faith in domestic institutions. Depending on the terms of the peacebuilding initiative and the institutional reforms called for, the level of outside training and capacity building will vary.

Trainers are often connected to international organizations or institutions whose mandates specifically focus on the capacity building of domestic practitioners carrying out TJ activities. For example, the Institute for International Criminal Investigations (IICI) is an international organization of professional investigators, military officers, lawyers and academics dedicated to training professionals in the investigation of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity, and to the deploying of teams of investigators to the scenes of war crimes around the world. Other international actors involved include the non-governmental International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) and the UN (in particular through the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, OHCHR) which has increased its presence in the field and developed practical tools on different components of transitional justice. The UN, its agencies and other outsiders, including non-governmental organizations (NGOs) usually focus on training judges, criminal investigators, lawyers, and truth commission practitioners, and more occasionally local activists. Insider organizations often take on the capacity training of those who will be implementing these mechanisms at the community level. Regional networks and NGOs developing regional programs such as the South African Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, have also been increasingly active in that domain. These networks and exchanges have helped to progressively develop and accumulate collective knowledge in that field.

National NGOs and community groups often carry out trainings and capacity building activities on TJ issues in their communities. These can range from training of victim advocates who collect testimony, to capacity building of human rights advocates. Trainings are often carried out in the form of seminars and workshops or longer term training programs and fellowships. The level of domestic capacity often determines the level of outsider involvement in training and capacity building.

Technical assistance, oversight and implementation of TJ mechanisms

If institutional reform is mandated by the peace-process, it may include oversight and implementation by an outsider organization such as the UN or donor agencies. For a lack of capacity and/or credit, local practitioners need sometimes to be replaced by outsiders who have handled similar investigations and processes in other post-conflict countries and are considered experts in their field. In less than two decades, a small community of experts has rapidly grown in that new field.

Research, education and exchanges

Education and academic exchanges are an important part of many national/local and external TJ organizations activities. A focus on best practices and improved understanding of the long term effects of TJ mechanisms has led to a proliferation of TJ education programs and practitioner and academic exchanges. As societies confront atrocities and engage TJ mechanisms, local practitioners become advisors and experts in their own right. Educational endeavours facilitate the diffusion of information from seasoned experts to new practitioners, allow for the sharing of best practices and facilitation of discussion over the long-term on the outcomes and effects of various TJ mechanisms, often in the form of conferences and fellowships. Several non-governmental and para-academic programs as well as networks that gather both academics and practitioners also encourage exchanges and reciprocal learning amongst societies that are considering, or have undertaken different mechanisms of transitional justice. Several listservs and blogs serve the same purpose and allow very lively exchanges on ongoing cases.

Go to Key websites

Another important aspect of education is the body of literature that has been developed about the TJ process itself. Academia has, and continues to generate a great deal of analysis on the conflict, human rights abuses and TJ mechanisms that inform policy makers and students of peacebuilding. Academic engagement with TJ issues aims to create a body of knowledge based on research that can inform future TJ processes and tailor each approach to the unique context of each transition. The body of literature that is created contributes to the establishment of an alternate narrative about the conflict, TJ and its outcomes. The recent creation of an International Journal of Transitional Justice has manifested the centrality of the topic as a sub-discipline, the importance to bridge the gap between scholars and practitioners, and facilitate sustained interaction across the range of disciplines encompassed by the topic of transitional justice. Yet, a deficit of empirical knowledge remains; more field research will need to be developed in the next few years to fill the gap. Go to Debates and Implementation Challenges

Awareness raising and the media

Many insider and outsider organizations have sought to raise public awareness on the transitional justice process itself. "The key to engendering effective and broad participation in transitional justice is to provide accurate information and facilitate deeper understanding. In most transitional country contexts, the media is the primary, and often only, channel of communication and public information. The more informed, accurate, and independent the media is about important transitional justice issues, the better equipped citizens are to become involved in the process, even if only as informed bystanders."29 International NGOs and associations of journalists are engaged in media trainings for local journalists.

Go to Public Information and Media Development

For local actors engaged in TJ processes, the use of media is an essential tool to convey information about the TJ justice process, its goals, mechanisms and results, in ways that are accessible to a broad audience who may not otherwise have exposure to the process.30 In addition, media is often used by TJ advocates as a tool to raise public awareness and promote civic participation. Truth commissions, in particular, seek to disseminate information and raise public awareness about their work. They also generally design a civic education program to promote citizen participation and involvement in national reconciliation. Educational efforts include local and national campaigns, workshops and seminars, and artistic and cultural events such as photography exhibits, concerts or street theatre.

Go to artistic and cultural endeavors

Multi-media education packages have also been developed by different actors. It is important to note that efforts to use media also rest on the use of dramatizations and other interpretations of events. "Audio-visual media, especially films, are often effective means of communicating to the general public about important subject matter. For some people, such media provide the first and perhaps only exposure to a topic."31 Go to Public Information and Media Development

Memorialization

Historical memory, a field that has developed in tandem with transitional justice and is deeply related to it, is the idea that efforts to collectively remember past human rights abuse and atrocity can contribute to a more democratic, peaceful, and just future. These efforts include public memorials, monuments, and museums about past human rights abuse, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide (or the social movements that sought to confront these evils), among many others. They consist of physical spaces that are places of mourning, and in some cases healing, for victims and survivors.32 Public acknowledgement and remembrance of atrocity is an act of collective recognition.33 It tells victims and survivors that the community/society values their humanity and recognizes the tragedy of what has occurred; it even honors them.34 In some circumstances, history and memorial work may also participate in a rehabilitation process for both survivors and victims. Memorialization comes into play both with respect to reparations and reparation. The increased recognition of memorialization within the transitional justice field is exemplified by recommendations of various truth commission reports, endorsing the idea of symbolic reparations in the form of memorials, sites of memory, commemorative days, the renaming of public facilities in the names of victims, and other artistic/cultural endeavors.35

More efforts will be needed to ensure that "truth commissions make better use of their proceedings and final reports to prepare countries for tasks that logically follow--incorporating the truth commissions' findings into educational programs and memorial projects designed to prevent future generations from forgetting the past and repeating its mistakes."36

Go to Memorialization, historiography and history education

Artistic and cultural endeavors

At the local grassroots level artistic endeavors such as theatre and oral histories, dance and music, and photographic and artistic exhibitions, have been used by communities and NGOs as alternative ways to contribute to the remembrance of the past, a complement or a facilitation of transitional justice processes. Arts-based processes may be creative methods to work through unresolved emotions and conflicting narratives, paving the way for new approaches that may impact an entire society.

In Peru, the Grupo Cultural Yuyachkani (a quechua word meaning "I am thinking/I am remembering"), working together with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, performed "outreach work in the communities where public hearings were to be convened by the Commission and 'lend the power of performance the arduous task of reconstructing and remembering the war.'"37 Their piece titled "Maria Cuchillo" was performed at the site of the first truth commission hearing in Huamanga and members of the troupe heard stories and took testimonials from those in the audience who had come to testify. A later piece called "Sin Título Técnica Mixta," echoed the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. It was shown to victims of the conflict who were displaced to Lima, the capital city.38

In El Salvador, the Central American University Simeon Cañas (UCA) has created a Truth Festival to bring together victims, human rights advocates, public servants and artists to reflect, exchange ideas and experiences and create processes of participation.39

In Burundi, the non-governmental organization RCN Justice & Démocratie has supported the production of three theatrical pieces written on the basis of the narratives of the actors themselves and several groups of the population, and played by actors from the three ethnic groups--Hutu, Tutsi and Twa. The representations took place all over the country and were followed by focus group discussions. The last piece has been created in preparation of the public auditions about the creation of a Truth commission in the country, as a facilitator of discussions about the historical abuses experienced by the different groups.40 Go to Case Studies: Memorialization, historiography and history education

[Back to Top]

Actors

A wide array of actors is currently involved in transitional justice in post-conflict societies. These actors can be international, national, mixed, or local, or some combination thereof. This section offers a brief presentation of the main stakeholders, giving a particular attention on national and local actors (insiders) and their interaction with outsiders.

Insiders

The main local and national actors involved in transitional justice processes are:

Representatives of the state

(the government, members of the legislative bodies and political parties) who may be solicited to pass a number of legislation.

Members of the justice system

(judges, lawyers, officers) who may be directly involved in some of the TJ processes and need specific support and training. Problems may arise when they are partly bypassed for lack of competency and credit.

Local staff of specialized transitional justice mechanisms

(such as hybrid courts, truth commissions) which may be, or not, in part constituted by members of the justice system; members of the local civil society are also often highly represented among this category.

National human rights institutions

(human rights commissions, ombudspersons offices) collect information about human rights abuses and crimes; if they already exist, they can directly inform the way TJ is carried out. In most cases, however, these institutions are recent or have not yet been created. In fact, in several cases, truth commission reports specifically recommended the establishment of national human rights institutions to act as a guarantor that the state and other actors will respect human rights, and also to monitor the progress of reforms to the security and justice institutions. Once transitional justice mechanisms are carried out and international scrutiny is relaxed, these institutions become a key mechanism of domestic accountability.

Human rights/civil society groups and organizations

(human rights NGOs, associations of lawyers, law academics, etc.) play a vital role at different stages of the process. Though prosecution of major perpetrators is a state responsibility, sometimes the efforts of civil society and victim groups provide the catalyst to persuade the state to act against impunity. For instance, in Guatemala, "each successful prosecution concerning military responsibility for atrocities against civilians in Guatemala succeeded only because civil society carried out most of the relevant investigations and appeared in court on behalf of the victims."41

Civil society groups are also instrumental in raising the awareness on TJ processes; monitoring the way they are put in place and work; transmitting information on cases they have documented; supporting the victims; facilitating the dissemination of the result of the processes, etc. They often play a crucial role at different stages of the establishment of TJ mechanisms; for instance, in both East Timor and Sierra Leone, civil society actors were involved in the selection of Commissioners. Local scholars and academic institutions can also play an important role, in particular in terms of advocacy, and as expert advisors. The case of the Human Rights Institute of the Central American University José Simeón Cañas (IDUCA) in El Salvador, exemplifies that role, reinforced in that case by the role the Jesuits have historically played in the local political arena. Another example is the Sierra Leone Court Monitoring Program, an independent monitoring program comprising human rights and civil society activists. Among civil society actors, local media and journalists also play a vital role to raise awareness and keep the general public informed of TJ processes.

Victims and survivors associations

They generally play a pivotal role in pushing for justice in the aftermath of gross human rights violations. One of the most well know victims advocacy groups, in a post-dictatorial context, was the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, a group of mothers whose children had been disappeared by the Argentine government. Since then, victims, their families and those advocating on their behalf, have had important roles in pushing for trials of human right abusers both domestically and abroad. In post-war countries, associations of victims have pushed for the prosecution of high-level perpetrators. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, the different associations of victims and survivors of Srebrenica massacres are well known for their action. In Chad, the Chadian Association of Victims of Political Repression and Crimes (AVCRP) partnered up with Human Rights Watch to push for the prosecution of former Chadian leader Hissene Habre in Senegal and Belgium.42

In other cases, victims are instead reluctant to take part in transitional justice mechanisms aimed at reparations or trials.43 Many associations of victims have also been formed to support individuals who have taken part in TJ processes and feel that their rights have not been recognized and protected, or have simply been forgotten. The case of the Khulumani Support Group in South Africa is an example of a large association of survivors and families of victims of the political conflict of South Africas apartheid past who have gathered to support each other in the process.44

Former combatants associations

They may also play a role, although their concerns revolve mainly around reintegration issues. They may also find themselves in a delicate position as potential low-profile perpetrators. In some countries, however, former combatants are found among members of victims and survivors associations.

Go to Security and Public Order: DDR

Traditional leaders and community organizations

They often play a significant role in demanding justice. "In Sierra Leone, the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was preceded by public workshops and conferences with strong civil society engagement, which helped to incorporate policies relating to children, women, and the involvement of traditional leaders in community reconciliation."45 Community groups can advocate for the implementation of TJ systems at the local level, emphasizing inclusion of community concerns in the larger context of TJ and at times demanding accountability for abuses when the central government lacks the will or power to pursue justice. This role is often undertaken with the support of local civil society groups.

Womens organizations

Among civil society and community organizations, womens organizations play an important role in pushing for and implementing transitional justice and helping to bring a gender perspective to TJ issues. "It is widely acknowledged that a significant number of victims of authoritarian regimes and conflict are women, and that they experience both in distinct ways. Similarly, women usually play a crucial role in the aftermath of violence such as: searching for victims or their remains, trying to reconstitute families and communities, upholding memory and demands for justice."46

Women, often victims of rape and other abuses have been pushed for the inclusion of crimes against women in the list of abuses to be addressed by the TJ process. Their role in situations as Serbrenica (Bosnia-Herzegovina), Liberia or Democratic Republic of Congo, has been crucial in that perspective. The mobilization of women organizations in obtaining the qualification of rape as a war crime has been central in the case of the International Criminal Tribunal of the former Yugoslavia, for instance. In Liberia, women also accounted for four of the initial nine commissioners of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). In Rwanda, ProFemmes/Twese Hamwe, a collective of 40 women's NGOs throughout the country, has been conducted a variety of projects to maximize womens participation in gacaca. These include advocacy for the integration of a gender perspective in implementation of the gacaca law and awareness-raising sessions for 100,000 women leaders, local government representatives and persons in detentioncentres.

Womens groups take part in a variety of activities, focused on raising awareness of abuses and calling for reparations. But they also play an important role in transitional justice at the local level as links between official processes and communities. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, "local womens groups were particularly active in counseling and materially supporting survivors of wartime abuses. Because they had already forged relationships with victims and survivors, members of these groups were in the position to serve as witnesses. Investigators spoke of Bosnian womens groups as important 'communication links' between The Hague and Bosnian people and, in many cases, as 'partners' in the investigation process."47 As women may have more difficulty accessing justice, their organizations are also often very active in the domain, both in an advocacy role and in providing direct support to women in need. As traditional and informal justice mechanisms have attracted increasing interest, women are also increasingly mobilized in raising awareness about potential bias against women, as many traditional justice mechanisms are structurally based on patriarchical power and help to reinforce it. Women also often play a protagonist role in ensuring that mental health and other dimensions of people psycho-social well-being be taken into consideration, and that these interventions are part of larger processes of social and political change.48

Go to Case Studies: Trauma, mental health and psycho-social well-being and Empowerment of underrepresented groups Women and gender issues

Religious organizations

The role of religious organizations in transitional justice varies, but in some cases, particularly in Latin America, religious affiliated organizations have played a central role in transitional justice processes.49 In several instances such as Peru, Guatemala and South Africa, respected religious leaders have been included on Truth Commission panels or have been brought on as official observers. In other contexts religious institutions, and not individuals, have played a central role in the TJ process. In Guatemala, the Archbishops Human Rights Office was deeply involvement in Guatemala's truth seeking efforts and established the Recovery of Historical Memory project (REMHI), in addition to, and in advance of the of, the official truth commission mandated by the Peace Accords.50 Go to Religion and Peacebuilding

Outsiders

Historically, the United Nations has been the leading international actor engaged in transitional justice. Its activities include setting up ad hoc tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, assisting with the establishment of truth commissions, and conducting vetting processes in UN-led multi-dimensional peace operations.51 Different UN programs and agencies are particularly involved in these endeavors, in particular UNDP and UNHCHR. Other multilateral institutions, such as the World Bank, and donors are also increasingly interested in transitional justice efforts due to recognition that in post-conflict societies justice issues are closely linked to prospects for economic development.

Since the mid 1990s, numerous NGOs, university-affiliated research centers, and professional networks specializing in transitional justice have come into existence. Prominent examples include the New York-based International Center for Transitional Justice and the South African Center for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. Prominent transnational human rights civil society organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International continue, of course, to play a role on that matter. A number of specialized projects, data bases and networks have also been created. Go to key websites

The interaction between insiders and outsiders

Experts on transitional justice (TJ) processes, often practitioners who have taken part in similar processes elsewhere, have played an increasing role in the development of the field in the last two decades. For instance, they influence the strategic choices to be made in terms of different institutional options, and the preparatory steps to be followed. When local judiciary personnel lack competence and legitimacy, they take part in the training of judges, law enforcement and investigations. In international and hybrid bodies, they are in key positions. The presence of outsiders can lend legitimacy to national actors who may have been discredited by the conflict; their expertise may give more credit to the process. One downside of it is that it can also perpetuate the image of domestic incompetence and lack of faith in domestic institutions. A tension also often exists between the goals and expectations of outsider experts and those of their domestic counterparts. Though the UN often stresses the importance of outsiders playing a facilitative role in what should be a nationally-driven agenda,52 reforms are sometimes carried out as negotiation between the domestic set of priorities and models and those of the donor.

This dilemma is even more acute for non-judiciary mechanisms such as truth commissions, for which members of local civil society organizations, representatives of local governments and members of the commissions themselves may have even more direct claims in terms of local ownership. Exchanges on blogs or networks of transitional justice researchers often reflect this cleavage (see for example the case of the work of the Liberia TRC in September 2008: http://listserv.aaas.org/mailman/listinfo/tjnetwork). Other online discussions about enduring dilemmas faced by truth commissions also reflect that dichotomy between insiders and outsiders views. However, this should not be reified or further over-simplified, but rather seen as reflective of the power relations in a particular setting.53 What is actually at play here, is not only the capacity for survivors to access the truth mechanisms but "the broad participation of victims and other citizens in the process of designing as well as implementing programmes of transitional justice."54

Go to Introduction to Peacebuiding: insiders vs. outsiders and Key debates and implementation challenges: local and global approaches

1. United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Rule-of-Law Tools for Post-Conflict States: Prosecution Initiatives (New York and Geneva: United Nations, 2006), 1.

2. Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Entered into force 1 July 2002, art. 17.

3. OHCHR, Rule-of-Law Tools for Post-Conflict States: Prosecution Initiatives 2.

4. Louise Mallinder, "Can Amnesties and International Justice be Reconciled?" International Journal of Transitional Justice 1, no. 2 (July 2007), 209-210.

5. Kristen Campbell, "The 'New Law' of Transitional Justice" (International Conference "Building a Future on Peace and Justice," Nuremberg, Germany, June 25-27, 2007.

6. Graeme Simpson, "A Snake Gives Birth to a Snake: Politics and Crime in the Transition to Democracy in South Africa," in Justice Gained? Crime and Crime Control in South Africa's Transition, eds. Bill Dixon and Elrena van der Spuy (Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press, 2004).

7. Eric Brahm, "Uncovering the Truth: Examining Truth Commission Success and Impact," International Studies Perspectives 8, no. 1 (2006): 16.

8. Priscilla B Hayner, Unspeakable Truths: Facing the Challenge of Truth Commissions (New York and London: Routledge, 2002), 17.

9. For an analysis of the South African TRC, see Andrew Rigby, Justice and Reconciliation: After the Violence (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001), 123-145.

10. Eduardo Gonzalez Cueva, "The Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the challenge of impunity," in Transitional Justice in the Twenty-First Century: Beyond Truth versus Justice, eds. Naomi Roht-Arriaza and Javier Mariezcurrena (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 70.

11. Mark Freeman and Priscilla B. Hayner, "Truth-Telling," in Reconciliation after Violent Conflict: A Handbook, eds David Bloomfield, Teresa Barnes, and Luc Huyse (Stockholm, Sweden: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2003), 127.

12. Ibid, 127-128.

13. Ibid, 132-138.

14. United Nations Security Council, The Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies Report of the Secretary General, S/2004/616 (August 23, 2004), 18-19, para. 54.

15. Pablo De Grieff, "Addressing the Past: Reparations for Gross Human Rights Abuses," in Civil War and the Rule of Law: Security, Development, Human Rights, eds. Agnes Hurwitz and Reyko Huang (Boulder and London: Lynne Rienner, 2008), 170-171. See also Pablo De Grieff, ed. The Handbook of Reparations. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

16. Stef Vandeginste, "Reparation," in Reconciliation after Violent Conflict: A Handbook, 148.

17. Paul Van Zyl, "Promoting Transitional Justice in Post-Conflict Societies," in Security Governance in Post-Conflict Peacebuilding, eds. Alan Bryden and Heiner Hanggi (Geneva: Geneva Center for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF), 2005), 211.

18. De Grieff, "Addressing the Past: Reparations for Gross Human Rights Abuses," 182.

19. Ibid, 181.

20. United Nations Security Council, The Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies, 18-19, para. 54.

21. De Grieff, "Addressing the Past: Reparations for Gross Human Rights Abuses," 182.

22. Ibid, 182-183.

23. Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, "Expanding the Boundaries of Transitional Justice," Ethics and International Affairs 22, no. 2 (Summer 2008): 215.

24. Ibid.

25. Pablo De Grieff, "Vetting and Transitional Justice," in Justice as Prevention: Vetting Public Employees in Transitional Societies, eds Alexander Mayer-Rieckh and Pablo de Greiff (New York: Social Science Research Council, 2007), 526.

26. Ibid, 527-528.

27. Roger Duthie, "Introduction," in Justice as Prevention: Vetting Public Employees in Transitional Societies, eds. Alexander Mayer-Rieckh and Pablo de Greiff (New York: Social Science Research Council, 2007), 18.

28. Ibid, 20.

29. Julia Crawford, Reporting Transitional Justice: A Handbook for Journalists (BBC World Services Trust and International Center for Transitional Justice, 2007).

Lawrence Randall and Cosme R. Pulano, "Transitional Justice Reporting Audit: Review of Media Coverage of the Truth and Reconciliation Process in Liberia," The Liberia Media Center (LMC), 2008.

31. For an inventory of media resources (in particular films and documentaries) related to Transitional Justice and Human Rights, see "Transitional Justice and Related Human Rights Media."

32. Ereshnee Naidu, The Ties that Bind: Strengthening the links between memorialisation and transitional justice (Center for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, 2006); and the ICTJ website.

33. Brandon Hamber, "Public Memorials and Reconciliation Process in Northern Ireland," Paper presented at the "Trauma and Transitional Justice in Divided Societies" Conference, Airlie House, Warrington, Virginia, USA, March 27-29, 2004, citing Sanford Levinson, Written in Stone: Public monuments in changing societies (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 1998), 63.

34. Judy Barsalou and Victoria Baxter, "The Urge to Remember: The Role of Memorials in Social Reconstruction and Transitional Justice," (United States Institute of Peace: Stabilization and Reconstruction Series No. 5, January 2007), 4.

35. Naidu, The Ties that Bind: Strengthening the links between memorialisation and transitional justice.

36. Barsalou and Baxter, "The Urge to Remember: The Role of Memorials in Social Reconstruction and Transitional Justice."

37.See Resisting Amnesia: Yuyachkani, Performance, and the Postwar Reconstruction of Peru; and Arte y transformacion de conflictos: El teatro y la transformacin de conflictos en el Perú, an investigation on this theatre experience and another conducted in the region of Ayacucho, the most affected by the war violence and also the place where the war first irrupted.

38. Ibid.

39. Instituto de Derechos Humanos de la UCA.

40. See Beatrice Pouligny, Théâtre & Justice au Burundi (Paris: CERI-Sciences Po/CNRS and Washington, DC: Georgetown University School of Foreign Service, 2007).

41. "Statement by International Center for Transitional Justice," UN Headquarters, New York, 22 June 2004 (Civil Society Observer, Volume 1, Issue 3, June-July 2004).

42. See Reed Brody, "The prosecution of Hissene Habre: International accountability, national impunity," in Transitional Justice in the Twenty-First Century: Beyond Truth versus Justice.

43. Jessica Berns and Abdul Wahab Musab, "Reflection: What We Have Learned from Working together at the Intersection of Transitional Justice and Coexistence," Transitional Justice Monitor 1, no. 2 (July 2008).

44. See Beatrice Pouligny, Shirley Gunn, and Zukiswa Khalipha, "Breaking the Silence: A Luta Continua. An art project about memory and healing in post-Apartheid South Africa" (Cape Town,, South Africa: Human Rights Media Centre, 2007).

45. "Statement by International Center for Transitional Justice."

46. "Gender and Reparations: Opportunities for Transitional Democracies?" (International Center for Transitional Justice, July 2008).

47. Sanam Naraghi Anderlini, Camille Pampell Conway and Lisa Kays, "Transitional Justice and Reconciliation," in Inclusive Security, Sustainable Peace: A Toolkit for Advocacy and Action (Hunt Alternatives Fund 2007).

48. Lisa Laplante, "Women as Political Participants: Psychosocial Postconflict Recovery in Peru," Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 13, no. 3 (2007).

49. For a discussion about the role of religion in transitional justice, see Daniel Philpott, "Religion, Reconciliation, and Transitional Justice: The State of the Field" (Social Science Research Council Working Papers, October 2007); see also Daniel Philpott, "What Religion Brings to the Politics of Transitional Justice," Journal of International Affairs 61, no. 1 (2007): 93-110 and Daniel Philpott, ed., The Politics of Past Evil: Religion, Reconciliation, and the Dilemmas of Transitional Justice (Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press, 2006).

50. Oliver Mazariegos, "The Recovery of Historical Memory Project of the Human Rights Office of the Archbishop of Guatemala: Data Processing, Database Representation," in Making the Case: Investigating Large Scale Human Rights Violations Using Information Systems and Data Analysis, eds. Patrick Ball, Herbert F. Spirer, and Louise Spirer (Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2000).

51. For a discussion about the transitional justice activities of the United Nations, see United Nations Security Council, The Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies.

52. See in particular the United Nations Security Council, The Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies; The same emphasis is given in the series of Rule-of-Law Tools for Post-Conflict States, published bythe United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

53. Roberta Culbertson and Batrice Pouligny, "Re-imagining Peace After Mass Crime: A Dialogical Exchange Between Insider and Outsider Knowledge," in After Mass Crime: Rebuilding States and Communities, eds. Pouligny, et al. (Tokyo/New York/Paris: United Nations University Press, 2007), 271-287.

54. Diane F. Orentlicher, "Settling Accounts Revisited: Reconciling Global Norms with Local Agency," International Journal of Transitional Justice 1, no. 1 (2007): 10-22.