Introduction: Economic Recovery Strategies: Definitions & Conceptual Issues

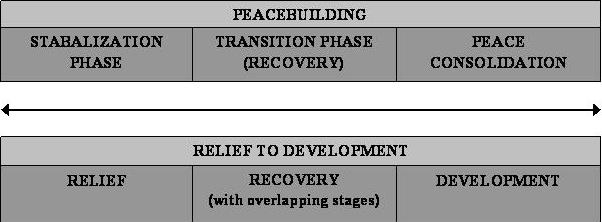

This section explores the concepts used by practitioners, scholars, and international organizations to address issues of economic recovery in post-conflict contexts. The concepts are considered within conceptual debates about the relief to development continuum, as well as within the context of stabilization and peace consolidation. Concepts that seek to define and measure national production and human welfare are touched upon, as they underlie and inform economic recovery choices and have important implications for peacebuilding. Further discussion of the institutional use of economic recovery-related concepts can be found in the "Actors" and "Activities" sections.Economic recoveryEconomic recovery at its core focuses on closing the gap between relief and development in a post-conflict setting. Central to understanding economic recovery is the recognition that, first, its challenges are unique to each country and, second, the post-conflict economy is not simply a "normal" economy in distress.1 While conditions manifest differently in different contexts, violent conflict often leaves behind substantial loss of livelihoods, loss of employment and incomes, debilitated infrastructure, collapse of institutions and rule of law, continuing insecurity, and fractured social networks. There is often an increase in subsistence agriculture and informal economic activities, and post-conflict countries "face serious macroeconomic problems including massive unemployment, moderate to high inflation, chronic fiscal deficits, high levels of external and domestic debt and low domestic revenues."2Economic recovery can be viewed from several perspectives. At the most narrow economic viewpoint, recovery is defined as "a return to the highest level of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita attained during the five years preceding the conflict."3 However, this measurement has limitations, as pre-conflict growth rates may have been very low or negative. Therefore, countries would want to exceed this marker, rather than return to old levels of economic development. In addition, the idea of human development is not considered in this perspective, nor are the complexities of the post-war economy. Efforts to conceptualize economic recovery as "re-creating" a viable economy after prolonged conflict,4"restoring basic capacities,"5 have given way to recognition that in many cases it is not desirable to go back to what was there before. It often is preferable to completely transform the economy. A new United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) report titled Sustaining Post-conflict Economic Recovery: Lessons and Challenges is premised on this recognition. Economic Recovery "Terms such as 'recovery', 'reconstruction', and 'rebuilding' might suggest a return to the status quo before the conflict. Typically, however, developmental pathologies such as extreme inequality, poverty, corruption, exclusion, institutional decay, poor policy design and economic mismanagement will have contributed to armed conflicts in the first instance and will have been further exacerbated during conflict. Accordingly, post-conflict recovery is often not about restoring pre-war economic or institutional arrangements; rather, it is about creating a new political economy dispensation. It is not about simply building back, but about building back differently and better. As such, economic recovery . . . is essentially transformative, requiring a mix of far-reaching economic, institutional, legal and policy reforms that allow war-torn countries to re-establish the foundations for self-sustaining development." Source: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Crisis Prevention and Recovery Report 2008: Post-Conflict Economic Recovery: Enabling Local Ingenuity. New York: UNDP, October 2008, 5. Economic recovery recognizes the limitations and challenges of the post-conflict economy and seeks to transform these conditions through economic, institutional, legal, and policy reform to build the foundation necessary for long-term development.6 In addressing the reliefdevelopment gap, it strives to build upon humanitarian programs and ensure their inputs become assets for longer-term development. This transition is understood not as a handover, but rather as "a process of identifying development needs and beginning the work of recovery as early as possible, drawing upon existing development resources and creating new, appropriate and adapted resources for development to respond to these needs."7 For many scholars and practitioners, the concept of economic recovery is intertwined with other concepts, which makes untangling it a conceptual challenge. Tony Addison, deputy director of the United Nations University's World Institute for Development Economic Research (UNU-WIDER), for example, views broad-based recovery as something that "improves the incomes and human development indicators of the majority of people, especially the poor."8 It involves both political reform (i.e., rewriting the constitution, introduction of multi-party elections, and decentralization of power) and economic reform (i.e., economic policy reform, public expenditure reform, revenue reform, trade and currency policy reform, and financial sector reform) strategies. Both must be undertaken in conjunction with a reconstruction agenda. Addison distinguishes between narrow versus broad-based recovery. Unless communities rebuild their livelihoods, neither reconstruction nor growth will be broad based. Communities cannot prosper unless private investment recreates markets and generates employment. A framework of development policy is needed to lower uncertainty and encourage long-term investment by communities, the private sector, and the state. Neither communities nor the private sector can realize their potential without a development state--one that wields legitimate power and is dedicated to broad-based recovery.9 The new UNDP Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery (BCPR) report has suggested that when the definition of economic recovery is so "maximalist" as to encompass all aspects of socioeconomic well-being, "such a . . . definition runs the risk of conflating recovery from conflict with overcoming underdevelopment more broadly."10 At the same time, BCPR accepts the notion that economic recovery must be "broad based" and "inclusive"; that it is critical for avoiding the recurrence of violence, which is a requirement for human development. The report focuses on identifying "indigenous drivers" to "provide the most viable platform on which to base post-conflict recovery efforts and international support."11 Go to Peace processes and debate, Strategies/models Economic recovery involves a range of activities, viewed somewhat differently by scholars and practitioners. It broadly covers a range of programmatic and policy-related efforts to jump-start the economy and rebuild and/or transform the institutions upon which that recovery depends, and in a way that serves peace. Relief to developmentTraditionally, conflict and post-conflict activities have been viewed through a paradigm that describes specific and delineated stages and roles for actors. Humanitarian relief has been viewed as appropriate for meeting emergency needs, such as food and shelter, during the conflict. Once a peace agreement has been signed, humanitarian actors, like the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), have handed over the longer-term recovery strategies to development actors, such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).It is often difficult to determine, however, when conflict has actually ended and a country can be designated as post-conflict. According to UNDP, "In some situations, conflicts recur after a short period of peace. In other cases, some violence continues even when conflict has ostensibly ended. There is often no easy 'before' and 'after.'"12 Janvier Nkurunziza of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) identifies two markers that can be used to determine the "end" of conflict: (1) a landmark victory by one of the warring parties, such as the fall of a capital city, as occurred in Ethiopia in 1991, or (2) the signing of a comprehensive peace agreement, which may not end all violence but usually significantly decreases it.13 Similarly, literature on peacebuilding increasingly recognizes that there are not steadfast phases between the end of conflict, immediate humanitarian relief, economic recovery and reconstruction, and longer-term development. In reality, all of these agendas overlap and should complement one another. When this does not happen, a so-called "relief to development" gap is created. When activities are implemented with a long-term view along a continuum, rather than sequential stages, relief can serve a developmental role and longer-term development thinking can inform humanitarian policy.14 The following diagram, drawn from noted works, aims to situate the relief to economic recovery continuum within the broader peacebuilding context. While some degree of phasing is inevitable, the phases should not be understood as "hard" phases with distinct boundaries, but rather as overlapping and interactive. Phasing is always likely to be contentious; there remain different interpretations of particular meanings of these terms relating to when they occur, as well as their overall content (i.e., many will view the relief to development continuum as a pillar of peacebuilding). Moreover, as highlighted by a new New York University Center on International Cooperation (CIC) report on early recovery, there is fluidity with time periods. A peace agreement can occur before or after the cessation of hostilities; therefore, certain activities may be possible in geographic areas that are less conflict-affected, irrespective of the status of the peace.  Sources: The peacebuilding continuum is an abridged version of that within: United Nations Peacebuilding Support Office. Measuring Peace Consolidation and Supporting Transition. New York: United Nations, March 2008, 5. The relief to development continuum draws from: Macrae, Joanna. Aiding Peace . . . and War: UNHCR, Returnee Reintegration, and the Relief-Development Debate. London: Humanitarian Policy Group, Overseas Development Institute, December 1999), 9; United Nations, Transition from Relief to Development: Key Issues Related to Humanitarian and Recovery/Transition Programmes (Rome: Secretary-Generals High-level Panel on UN System-wide Coherence in the Areas of Development, Humanitarian Assistance, and the Environment, May 19, 2006), 2. While "stabilization" is associated with military operations and political/security-oriented action, "transition" remains somewhat ill defined.15 The United Nations (UN) refers to the period between the immediate aftermath of a crisis and the restoration of pre-crisis conditions (or what it terms recovery) or improvement to an acceptable level (called development) as the "transition phase": "Transitions are characterized by a shifting emphasis from life-saving to restoring livelihoods, achieving the internationally agreed development goals, including the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and by an increasing reliance on national ownership through national development strategies."16 A recent Peacebuilding Support Office (PBSO) briefing paper suggests four types of transition within the context of UN thinking about when it should depart from a post-conflict setting: (1) the closure or significant downgrading of peace operations; (2) the shift from a largely humanitarian response to an approach that emphasizes reconstruction and development; (3) the phasing out of direct UN-led assistance (executive mandate and direct execution modalities) in favor of country-led consolidation efforts (assistance mandate and national execution modalities); and (4) the "migration" of a country from the Peacebuilding Commissions peacebuilding agenda.17 Despite broad recognition that early recovery interventions should commence during the relief phase,18 the post-conflict environment poses several barriers to this work in the transition phase, such as in severely weakened states. There are also extraordinary challenges in coordinating organizations and governments, as the "architectures of relief and development assistance differ in many respects" and organizations are often limited to certain activities by their mandates. The UN and other international institutions are increasingly developing strategies for addressing the gap, such as the Consolidated Appeals Process, which seeks to provide funding during the transition from relief to early recovery. However, there are serious faults in these mechanisms.19 In addition, despite increasing attention to the concept of a relief to development continuum and economic recovery, there are still debates over the best strategies for addressing these issues. These debates are discussed in more depth later in this sub-section. [Back to Top] Related conceptsEconomic recovery, economic reconstruction, economic rehabilitation, and economic reform are frequently used interchangeably or are conflated, depending on how one views the terms.20 In many cases, organizations choose a specific term that is defined in terms of their mandate.21 For example, the European Commission (EC) uses reconstruction and rehabilitation, and the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) use post-conflict reconstruction and recovery. Bilateral donors also implement based on different conceptual understandings. Go to Main ActorsAs evidenced by the previous definitions of recovery-related concepts, there is significant overlap in and conflation of the use of these terms. The following chart illustrates this issue.

Early recoveryEarly recovery is still considered a relatively new conceptone that is in need of greater attention and clarity. UNDP identifies early recovery as addressing a critical gap in coverage between humanitarian relief and long-term recovery, between reliance and self-sufficiency.24The CIC study describes the usage of the term "early recovery" as "diverse and confused," with it referring to response to disaster and conflict, to phases prior to the cessation of hostilities, and often (loosely) to much later action. While the study points out that the definition as used by UNDP is more focused on the socio-economic elements of recovery rather than the political and security elements, CIC argues for a broader notion that seeks to address gaps in early efforts to secure stability and establish peace; to address economic and social factors by resuscitating markets, livelihoods, services, and the state capacities necessary to foster them; and, finally, to build core state capacity to manage political, security, and development processes. Economic reconstructionThe term "economic reconstruction" is used in a broad sense to describe not only the reconstruction process itself but also, as noted by Graciana del Castillo, "all the policy measures, including stabilization and structural reform as well as institutional and capacity building activities, necessary to reactivate the economy and bring it to a sustainable development path."25 Reconstruction strategies therefore address the socio-economic conditions in a particular country and the access to external financing required for the reestablishment of production and trade. Hunjoon Kim notes, "Special care is necessary to address the main concerns of macroeconomic policies. Introducing effective macroeconomic management is related to creating the right framework for international assistance."26According to a major study of peacebuilding concepts and usages led by Michael Barnett, the term "economic reconstruction" is grouped with social, developmental, and humanitarian reconstruction and is defined as "aid for physical reconstruction of buildings, utilities, and structures."27 The World Bank, the United States Department of State, the United States Department of Defense, and the United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office (UKFCO) use this term with varying definitions, including those outlined in the chart above.28 Some refer more broadly to a "reconstruction agenda." A volume put out by Tony Addison identifies this as including "a daunting range of tasks--everything from conflict resolution to peace-enforcement to demobilization to shifting public money from the military and into development (to cite just four priorities). It is accompanied by, and interacts with, the agendas of economic and political reform."29 Economic rehabilitationThe European Union (EU) is among those that favor the concepts of "rehabilitation" and "reconstruction," which pertain to the "reestablishment of a working economy and institutional capacity."30A groundbreaking work by Krishna Kumar in the late 1990s conceptualized economic "rehabilitation broadly to encompass reform and reconstruction, with three interrelated elements," restoration, structural reform, and reconstruction.31 The terms "rehabilitation," "reconstruction," and "rebuilding" are used interchangeably in that "all refer to the efforts to rebuild political, economic and social structures of war-torn societies."32 Jeroen de Zeeuw of the "Clingendael" Institute discusses rehabilitation programs as "large-scale reconstruction programme(s) to reinvigorate the economic structures of a particular country," focusing in particular on physical infrastructure and recovery of social and economic systems in the form of schools, houses, food supplies, and stable currencies. This type of rehabilitation was introduced into the international lexicon with the Marshall Plan following 1947 and has continued to dominate "contemporary thinking on rehabilitation."33 However, "apart from humanitarian aid, most donor countries seem to be reluctant to commit themselves to long-term rehabilitation programmes. . . . For this reason alone, the repetition of a Marshall Plan for contemporary 'post-conflict' settings seems highly unlikely."34 Human securityHuman security introduces a new paradigm that links security and development, essentially prioritizing the security of individuals over the security of states. It joins the two as mutually dependent, as security relies on more than just traditional approaches to economic recovery, which usually consist of liberalization, privatization, and macroeconomic policies. It argues that separate treatment of these issues can actually worsen the root causes of conflict, and instead advocates for a new conceptual framework that combines human rights with human development.35The scope of the concept ranges from more narrow to more broad interpretations. The narrow view, first offered by the Canadian government, protects against violent legal and physical security threats to individuals (possibly including genocide, torture, slavery, inhuman treatment, and grave violations of human rights, as per the International Criminal Court statute).36 The broad UNDP definition is freedom from fear and freedom from want. This broader notion protects against critical and pervasive threats to individuals and communities, including political, civil, social, economic, and cultural factors that endanger security. It encompasses human rights, good governance, and access to economic opportunity, education, and healthcare.37 Some scholars, like Mary Kaldor, take a middle path, suggesting that human security is fundamentally about reducing extreme vulnerabilities.38 Amartya Sen concludes it to be narrower than human rights or development, and rather about the "downside risks" that threaten daily human survival. Kaldor suggests it is based on five core principles: the primacy of human rights, legitimate political authority, the principle of multilateralism, a bottom-up approach, and a regional focus. It purports to address the causes of conflict and the deeper causes of insecurity.39 This aim is rooted in a new concept of development and economic recovery that advocates for institution building, promoting alternative livelihoods, and curtailing illicit commerce and the trade of illegal arms. The implications of this new concept are a greater investment in development assistance tied to conflict prevention policy development, civil society engagement, and local ownership of processes, legitimate employment, and long-term livelihoods. These activities elevate the social and economic well-being of the individual over macroeconomic stabilization and growth, both of which, its proponents argue, are false indicators of risk factors.40 Human security is thought to be the framework through which sustainable peace can be achieved. [Back to Top] StatebuildingEconomic recovery is often viewed as a component of statebuilding, which itself is at the heart of building a durable peace and human development and the subject of an expansive and growing literature.41 Statebuilding involves the "rebuilding or establishing at least minimally functioning state institutions."42 As highlighted by Charles Call and Elizabeth Cousens, for some, statebuilding should focus on institutions to ensure law, order, and repression of resurgent violence. For others, it implies a focus on the institutions of decision making and legitimation, and, for still others, it involves the very foundations of economic recovery in the form of revenue generation, rule of law, and the creation of an investment environment.43The ability of the state to collect and manage public resources is at the heart of statebuilding,44 a core aspect of economic recovery. James Boyce and Madalene O'Donnell argue that there is a two-way relationship between state legitimacy and revenue collection, as both are dependent on the other to succeed.45 More generally, without functioning and legitimate state institutions, post-conflict societies are much less likely to escape violence and poverty.46 Go to Public Finance and Economic Governance An Overseas Development Institute (ODI) report underscores the economic components of statebuilding, arguing that an effective state has 10 core functions it must perform, five of which are concerned with economic policy:47

[Back to Top] Measures of national production and human welfareConcepts that seek to define and measure national production and human welfare are introduced here, alongside human development itself and the Millennium Development Goals, because of their conceptual and practical linkages with economic recovery. These concepts and measures inform choices, explicitly or implicitly, made in economic recovery, with wider application to and implications for peacebuilding. They often underlie assumptions and debates, and arguably need to be referenced more explicitly and debated in connection with economic recovery aims and requisite strategies.Gross domestic product (GDP)According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), "Gross domestic product is an aggregate measure of production equal to the sum of the gross values added of all resident institutional units engaged in production (plus any taxes, and minus and subsidies, on products not included in the value of their outputs). The sum of the final uses of goods and services (all uses except intermediate consumption) measured in purchasers' prices, less the value of imports of goods and services, or the sum of primary incomes distributed by resident producer units."50The United Nations defines GDP a bit more succinctly: "GDP is the total unduplicated output of economic goods and services produced within a country as measured in monetary terms according to the United Nations System of National Accounts (SNA)."51 GDP as a measurement of human welfare is often critiqued for its lack of attention to distributive concerns and a focus on income. According to UNDP, "Comparing rankings on GDP per capita and the HDI can reveal much about the results of national policy choices. For example, a country with a very high GDP per capita such as Oman, which as a relatively low level of educational attainment, can have a lower HDI rank that, say, Uruguay, which has roughly 60% of the GDP per capita of Oman."52 Human developmentHuman development is described by its founder Mahbub ul Haq as the "enlargement of all human choiceswhether economic, social, cultural or political."53 The emergence of this paradigm in the 1980s was a significant departure from the economic growth school of thought, although its roots are the teachings of Aristotle, Immanuel Kant, Adam Smith, and Karl Marx.54As expanded upon in the 2006 Liberia National Human Development Report, in addition to "enhancing people's choices and access to life-sustaining opportunities"55 human-centered development means that "people are the primary targets of the process and therefore the prime benefactor of development efforts and outcomes."56 Human development includes both "evaluative" and "agency" aspects--"the former means improving human lives as an explicit development objective, while the latter refers to what people can do to improve their lives through individual, social and political processes."57 The elements of human development are described as: social progress (greater access to knowledge and better nutrition and healthcare); equity (distributive justice and fair distribution of incomes and assets through equal access to opportunities); sustainability (concern for not only present but also future generations); security(from conflict and against disease, hunger, unemployment, displacement, famine, etc.); and participation (empowerment, democratic governance, gender equality, civil and political rights, cultural liberty, etc.).58 As underscored by UNDP, which has made it the conceptual foundation of the institution's development vision, the human development approach is holistic and integrated in that "it strives to find the balance between efficiency, equity and freedom and recognizes that there is not automatic link between economic growth and human progress."59 In its new economic recovery report, the Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery emphasizes that economic recovery is a requirement for human development.60 Alternatively, human development can be viewed as the paradigm that should normatively and practically inform economic recovery efforts. Human development index (HDI)According to the United Nations Development Programme, the human development index (HDI) "is a summary composite index that measures a country's average achievements in three basic aspects of human development: health, knowledge, and a decent standard of living."61 Health is measured by life expectancy at birth. Knowledge is measured by a combination of the adult literacy rate and the combined primary, secondary, and tertiary gross enrollment ratio. Standard of living is measured by gross domestic product at purchasing power parity per capita (PPP US$). (Purchasing power parities are the rates of currency conversion used to eliminate the differences in price levels between countries.)62The HDI is intended for use within the context of other measurements and assessments in facilitating an understanding of human development. The measurement, for example, does not reflect political participation or gender inequalities. The HDI and other composite indices can therefore only offer a broad proxy on some of the key issues of human development, gender disparity, and human poverty.63 Human development reports (HDR) provide country-specific HDI information. The HDR presents statistics in human development indicator tables, which provide a global assessment of country achievements in different areas of human development and statistical evidence in the thematic analyses in the chapters, which may be based on international, national, or sub-national data. The HDR also incorporates assessment of Millennium Development Goals indicators in the human development indicators tables.64 Other human development indices that can be found within the HDRs are the Gender-related Development Index (GDI), the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM), and the Human Poverty Index (HPI).65 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)The member states of the United Nations ratified the "Millennium Declaration" in September 2000 at the UN Millennium Summit, which recommitted the nations to UN goals and values and created a new dedication to reducing extreme poverty by 2015 by setting out a series of targets. These eight time-bound targets are now known as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and have become the platform for poverty eradication plans worldwide.66Considering links with human development, UNDP has highlighted that while the MDGs are considered human development goals, they do not reflect all of the key dimensions of human development:67 "The MDGs highlight the distance to be traveled; the human development approach focuses on how to reach these goals."68 Some critics argue that MDGs do not address structural issues and inequality, although they are intended to be pro-poor and to be linked with poverty reduction strategy papers.69 Millennium Development Goals (1) End poverty and hunger: Halve the proportion of people suffering from extreme poverty and hunger. (2) Universal education: Guarantee that all children complete primary school. (3) Gender equality: Ensure that girls have the same opportunities as boys. (4) Child health: Reduce by two-thirds a childs risk of dying before age five. (5) Maternal health: Reduce by three-quarters a mothers risk of dying from pregnancy-related causes. Halve the proportion of people without access to safe drinking water. (6) Combat HIV/AIDS: Stop and reverse the spread of HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis (TB). (7) Environmental sustainability: Protect the worlds ecosystems and biodiversity. (8) Global partnership: Ensure that rich counties grant steeper debt relief, more foreign aid, and fairer opportunities to trade. Sources: United Nations (UN). End Poverty 2015: Millennium Development Goals; Vandemoortele, Jan. The MDGs and Pro-Poor Policies: Can External Partners Make a Difference? Pretoria: Southern African Regional Poverty Network, December 2003). [Back to Top] Conflict sensitivityConflict sensitivitybroadly refers to the notion of systematically taking into account both the positive and negative impact of interventions, in terms of conflict or peace dynamics, on the contexts in which they are undertaken, and, conversely, the impact of these contexts on the intervention.70 Conflict-sensitive approaches to recovery, development, and any other sector, program, or policy, then, involve ensuring such efforts are undertaken with these considerations in mind. Conflict sensitivity is particularly important for early recovery and broader economic recovery. The CIC study points out, "The deeply political nature of post-conflict recovery cannot be overstated. Decisions that in normal development contexts have low costs can in early post-conflict contexts have serious repercussions, putting a premium on training and conflict sensitivity."71As noted by scholar practitioners Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and Erin McCandless, "Approaches concerned with 'conflict sensitivity' and conflict prevention . . . elevate the need for understanding the historical, social, political-economy conflict context, and for developing mechanisms to address them."72 James Boyce and Madalene O'Donnell provide one framework that can facilitate understanding of the contexts that need to be considered for the development of conflict-sensitive policies and strategies.

Similar to the Boyce/O'Donnell framework, a recent Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery report on economic recovery identifies contexts that differentiate conflict-affected countries: (1) countries may be differentiated by their level of per capita income, which can also influence infrastructure development, human and institutional capacities, aid dependence, and levels of indebtedness; (2) the extent that horizontal inequalities exist influences policy design and implementation, especially in the post-conflict context where these inequalities may have been a major cause of conflict; and (3) the presence or lack of natural resource abundance affects the financing of economic recovery efforts because countries with high revenues from natural resources will be more able to finance recovery efforts independently and attract foreign investment. However, the presence of natural resources has often been linked with conflict risks, like high levels of corruption and rent seeking.73 Go to Private Sector |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Print View

Print View